There are movie fans, there are film lovers, and then there are cinephiles – such as Butheina Kazim, founder and MD of Cinema Akil, a trailblazer in the heart of Al Serkal Avenue that has been bringing unconventional films to the city for the last three years. BroadcastPro ME talks to the woman behind Dubai’s only arthouse cinema.

Art, films and events were among the biggest commercial casualties of the pandemic as they came to an abrupt halt when the shutters were pulled down on thousands of creative businesses. Defying the odds, Cinema Akil pulled through bravely as Butheina Kazim, the creative mind behind it, poured her energy into devising alternate strategies. The intrepid entrepreneur not only galvanised the city’s only arthouse cinema through one of the most difficult periods in the entertainment industry, but also retained it at its current address in Al Serkal, as well as in the hearts of Dubai’s cinema lovers.

Born in 2014 out of a heady mix of passion for cinema, love for Dubai and a “little bit of insanity”, Cinema Akil is a labour of love. Derived from the Arabic word ’akal’, meaning the brain or mind, the name is meant to portray cinema as the embodiment of wisdom and intelligence. At the time, Dubai’s art and culture scene was rapidly unfolding with Al Serkal Avenue having gained a foothold, Art Dubai established, and art galleries mushrooming across the city.

![]() As Dubai’s cultural landscape shifted, Kazim noticed an evolution in cinema preferences. Numerous festivals such as the Dubai International Film Festival (DIFF), Abu Dhabi Film Festival and the Gulf Film Festival were emerging, stoking an interest in films that were alternatives to those showcased in legacy cinemas and multiplexes.

As Dubai’s cultural landscape shifted, Kazim noticed an evolution in cinema preferences. Numerous festivals such as the Dubai International Film Festival (DIFF), Abu Dhabi Film Festival and the Gulf Film Festival were emerging, stoking an interest in films that were alternatives to those showcased in legacy cinemas and multiplexes.

“We started Cinema Akil as an experiment. It was the heyday of the city’s bustling art scene,” she says. “Outside of the film festivals, there was no real chance to discover and access such films, even specialty films from the region.”

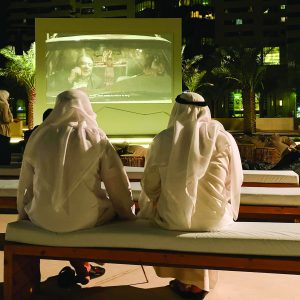

Kazim was convinced that “this had a lot of potential” and that the time was ripe to start the arthouse cinema movement in Dubai. Thus was born Cinema Akil. Starting off its journey as a ’nomadic cinema’, the pop-up cinema screened a variety of international films in different locations. Events were nonticketed, with free screenings made possible through sponsorships or commissions. Classics such as Alfred Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder, Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali and Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Like Father, Like Son were some of the first films to be screened.

“We started with a limited six-week programme featuring handpicked films. These were meant to be a kind of a smorgasbord of the programme Cinema Akil would showcase once it moved to a permanent location. From there, it was a spiral effect. A lot of people showed up – they were very interested and engaged. There was a lot of conversation and we knew we had tapped into something that was missing in the city,” says Kazim jubilantly.

From there, things started moving quickly. Together with Al Serkal Avenue, Cinema Akil’s embryonic partner, Kazim drew up plans for a full-time operational brick-and-mortar arthouse cinema. It would be another four years before her dream took shape at Al Serkal. “It took longer by intention, because we were benefiting from the experience of the nomadic set-up.”

The move to a 365-day setup was huge in terms of both programming and funding. For Kazim, Cinema Akil had never been a commercially-driven enterprise. Since its inception, the platform had gradually built up a “committed and captive audience” and an equally solid reputation. The move from the lean operational structure of a pop-up to a full-time set-up was not cheap, is all she divulges about the investment required.

“Through our corporate tie-ups and pop-up sponsorships, we were able to raise the capital needed. Having strong partnerships through the years helped to offset a lot of the initial start-up costs that we incurred,” she says.

But just as Cinema Akil was gaining popularity, the pandemic hit.

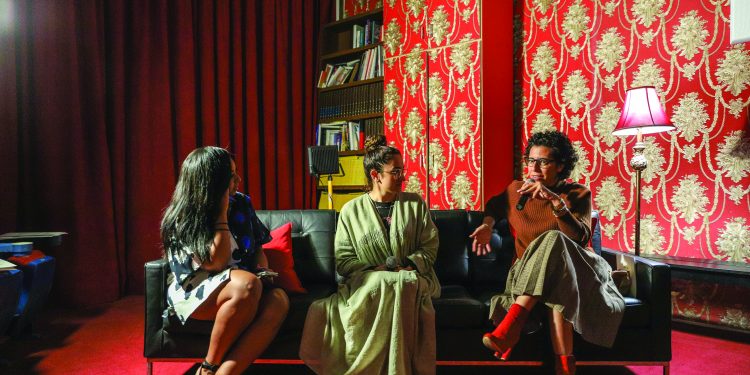

One element that helped Cinema Akil get through Covid-19 was its versatile interior. “The days of a dark room cinema and black box that operate only during screening hours are gone. Right from the beginning, it was very clear to us that we have to be more than a cinema. We designed Cinema Akil in a way that allows the space to be utilised for a lot of different activation and monetisation opportunities for our partners and clients. During the pandemic, this became a big focus for us – rentals as well as leveraging the space and footfall around us to create unique, memorable experiences for our clients.”

Cinema Akil’s shabby chic interiors, draped with damask patterned wallpaper, ooze old-world charm. Cinematic heritage appears in the form of the forty plush red seats salvaged from the Golden Cinema (Dubai’s longest-running single-screen theatre, which closed in 2017) that fringe the main hall on the left and right.

“We’ve always been feminists – it is in the DNA of Cinema Akil. We try to have a bigger representation of women filmmakers and give a platform to women’s voices, especially women of colour and from underrepresented communities” – Butheina Kazim, founder, Cinema Akil

While the ambience is reminiscent of a bygone era, the equipment is state-of-the-art. Kazim made sure the acoustic treatment was top-notch and the projectors the best in the industry. The middle of the hall features mismatched movable settees, a deliberate design element to allow Kazim’s team to configure the space as needed. “It was an intentional decision to have a space that we could play around with. The kind of malleability the interiors have allows them to transform very quickly for any kind of activity that’s suited for an intimate space and involves the use of a screen as part of its main experience.”

In addition to its infrastructural versatility and Kazim’s zeal, resilience also came from long-term allies. Al Serkal Avenue was supportive. The art and culture district opened up its outdoor space for Cinema Akil, allowing it to host alfresco screenings and create a unique ’under the sky’ screening experience. With indoor seating capped at 30%, the outdoor arrangement gave a much-needed impetus to ticket sales.

Kazim’s cinema is versatile but committed to movies. It has a finger on the pulse of its audience but also holds its own in the world of film. And this has been the recipe for its success. Truly unique, its approach isn’t something Kazim has copied from legacy theatres or modern multiplexes, and is symbolic of the changing face of the movie-going experience.

As its founder says, “The future of cinema is no longer the big screen, the multiplex or large tubs of popcorn. Those days are gone when one film screens across all the theatres and dominates the box office for four weeks or longer. Now it’s about understanding the community, building a relationship, and becoming part and parcel of the local experience that will sustain cinema.”

Community building was one of the reasons British arthouse cinemas were able to keep their projectors turning where large multiplexes failed. They were able to bounce back because people believed in the role they played in their communities. Kazim, too, has created a sense of community at Cinema Akil. “We have a very close and direct relationship with our audience. And this was something we designed from the get-go. The team isn’t there just to run the cash register or punch tickets. We are very interested in what we are doing.”

For Kazim, it’s not just content that is key, but also how it’s being presented. Kazim points to the time when Cinema Akil featured You Will Die at 20 and drew out the Sudanese diaspora. Then there was the controversial film Neverland, with a debate after the screening.

For Kazim, it’s not just content that is key, but also how it’s being presented. Kazim points to the time when Cinema Akil featured You Will Die at 20 and drew out the Sudanese diaspora. Then there was the controversial film Neverland, with a debate after the screening.

“There are different ways you can watch it, but there’s something about being able to watch it in your city on the big screen and then have a discussion about it in a public space – that is what we’re addressing. It’s a combination of all of these ingredients, and not just making the films available.”

At the time of this interview, Cinema Akil was running the Cinema of Commoning, a travelling programme of films collectively curated by cinemas in Berlin, Bangkok, Jakarta, Istanbul, Dubai, Santiago, Cluj and Luanda.

In the wake of the pandemic, OTT streaming services boomed, platforms and multiplexes, some films rely solely on platforms like Cinema Akil to reach their target audience. Kazim gives the example of Dog Man, Cold War, Pinocchio and Elizabeth – a Portrait in Parts (for which Cinema Akil has exclusive release rights in the UAE). It’s here that Cinema Akil’s relationship with distributors also comes into play. Over the years, Kazim has built up strong connections with distributors such as Gulf Films, Phars, Falcon Films, Four Star Films, Moving Turtle and Front Row Filmed Entertainment – the longest partnership. “We always had this shared belief that there’s an untapped market here. We’ve managed to bring films that, if we didn’t exist and they [distributors] didn’t exist, would probably never hit the screens here.”

However, films, a venue and a distribution network would all be useless if the target audience didn’t exist. “These kinds of films need a certain kind of appetite. It’s as if we are taking a bet on the taste of our audiences here.”

One of Kazim’s challenges in the early days was “understanding the audience here, and what their curiosities and interests entailed”.

“We sometimes forget how much richness comes from the different cultures in Dubai. People don’t talk about how much knowledge and cinema literacy comes in from all the countries that make up the population of Dubai. If you’re an Egyptian, you have the entire cinema history of Egypt in your consciousness. We have the opportunity, advantage and pleasure of reaching out to these different communities, speaking to them and bringing to them something that they trust. Some people come to watch a film because they’ve heard that Cinema Akil is showing it.”

Cinema Akil is also Kazim’s way of giving back to Dubai and the UAE. A member of the Network of Arab Alternative Screens (NAAS), it regularly showcases Emirati films, especially in its pop-up activations. In its first year of operation, Cinema Akil hosted a dedicated Emirati programme curated by filmmaker Khalid Al Mahmoud, and it has shown the majority of big Emirati films, including Abdulla Al Kaabi’s Only Men Go to the Grave. The closure of several film festivals in the UAE left a gaping hole in the Emirati film scene, as they were big parts of the support system in terms of funding structures, exhibitions and awards.

“We sometimes forget how much richness comes from the different cultures in Dubai. People don’t talk about how much knowledge and cinema literacy comes in from all the countries that make up the population of Dubai”- Butheina Kazim, founder, Cinema Akil

For Kazim, the “history of our time” and the way we “understand ourselves and cement things in our mind” are represented in film. “When you curtail the filmmaking cycle, there is a sort of loss of faith in the filmmakers and in the importance of what they are creating.” She calls for a stronger film ecosystem in the country through setting up film schools, festivals and even more arthouse cinemas.

In any Arab film programme that Cinema Akil puts together, it makes sure there’s an Emirati film. It has also taken Emirati films overseas, showcasing them at events such as Berlinale.

In any Arab film programme that Cinema Akil puts together, it makes sure there’s an Emirati film. It has also taken Emirati films overseas, showcasing them at events such as Berlinale.

Kazim is also mindful about using Cinema Akil as a platform to champion female Emirati filmmakers. While women filmmakers, actors and directors have higher representation in the UAE than in other Arab countries, she believes there is still a lot that can be done, and Cinema Akil is actively contributing to this.

“We’ve always been feminists – it is in the DNA of Cinema Akil. We try to have a bigger representation of women filmmakers and give a platform to women’s voices, especially women of colour and from underrepresented communities.”

Going forward, Kazim wants to “go back to the original plan of Cinema Akil … we had only one good year of full operations before we went into the pandemic. For the past two years, we’ve spent more time hustling and programming in survival mode, and a lot of our original plans to scale and develop were shelved. So this year is about delivering on that promise and going back to the basics, building infrastructure and creating new long-term opportunities for cinema experiences,” she says, signing off optimistically.