Egypt’s rich cinematic history, spanning over a century, faces imminent risk from decay. We look at how Egyptian Media Production City is spearheading a groundbreaking restoration project to restore its iconic films.

Egypt is a prolific producer of cinema with a history dating back to 1896, but this rich cultural heritage is at risk of being lost to the world if steps aren’t taken to rescue the archive from damage and decay. Egyptian Media Production City is undertaking a major project to restore, preserve and protect this precious film stock for future generations with the Cintel Scanner G3 HDR+.

By some reckoning, about three-quarters of the feature films produced in the Arab world have emanated from Egypt, with the 1940s to the 1960s generally considered the golden age of Egyptian cinema. In fact, in the 1950s Egypt’s cinema industry was the world’s third largest.

Egyptian Media Production City (EMPC) has a contract with the Ministry of Culture, which holds the original prints for hundreds of motion pictures and photographic treasures made between 1940 and the late 1990s, all shot on celluloid. In 2018, it established the Cinematic Restoration Centre (CRC), dedicated to documenting and digitising the entire collection.

“Cinema is a huge part of Egyptian culture, but time is running out to preserve that legacy,” explains CRC General Manager Nada Hossam El Din Farahat. “For decades celluloid was the principal recording media, and much of the original negatives are in poor condition and decaying rapidly. We have already lost a percentage of this stock, so we had to act fast.”

Work began in 2019 to restore news reel archive of the Egyptian Film Newspaper, covering the period 1952 to 2015. The entire 480-hour collection was restored and digitised over three years. Since then, the Centre has restored classic films Little Love, Much Violence (1995), Watch Out for Zuzu (1972) and Love in Karnak (1967), which were shown at the Red Sea International Film Festival.

Further restorations for the Cairo International Film Festival include the features Diary of a Deputy in the Countryside (1969) and A Song on the Passage (1972).

However, this still left more than 1,500 films untouched in the archive. The volume was simply too great and the risk of irretrievable damage too high.

However, this still left more than 1,500 films untouched in the archive. The volume was simply too great and the risk of irretrievable damage too high.

“We have always used Cintel for telecine at EMPC because we know it delivers the best image quality, but the machine we had was old and standard definition only,” explains Farahat. “In addition, we could not afford to rely on just one machine for all of our moving images, pictures and documents. We needed a technology that would be able to capture as much detail as possible, which is why it was a natural step for us to lead our preservation efforts with the latest Cintel scanner.”

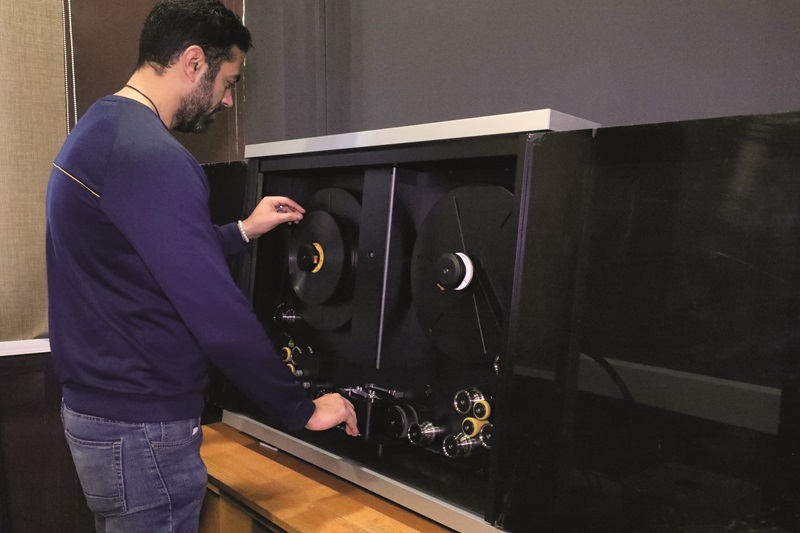

Installed by Cairo-based system integrator Systems Design and supported by Blackmagic Design regional distributor Media Cast, which also provided CRC with training, the Cintel Scanner G3 HDR+ is now being used on the next phase of the project to restore 300 iconic Egyptian feature films.

The process begins with CRC experts physically inspecting the reels and manually repairing all joints, holes, fractures and ruptures of the degraded negative. The repaired negative is cleaned to remove accumulated dirt, fingerprints and dust, then the reels are scanned in real time at 4K resolution.

In parallel, CRC uses the Cintel Audio and KeyKode Reader to record high-quality audio information from the negative in sync with picture scanning. These automatically correct for wow and flutter even as the scanner speeds change. In addition, KeyKode numbers identify individual film frames, dramatically speeding up post-production workflows. The scanned 4K files are then opened in DaVinci Resolve for colour, restoration and mastering work.

“What makes the Cintel Scanner G3 superior to other scanners is that it is linked to the DaVinci Resolve Studio. Information is automatically captured from Cintel and imported into DaVinci, saving a lot of time. Other systems do not do that,” Farahat says. “The combination of the Cintel scanner and DaVinci Resolve always gives CRC’s team of six colourists the widest dynamic range to assist in restoring the look of the films.”

In addition to advanced colour correction, DaVinci Resolve Studio also features tools for automatic dirt removal, dust busting, deflickering, spot patch repair with smart fill technology, and advanced temporal and spatial noise reduction.

“Even after being repaired and cleaned, the film retains many scratches and dust which the high-resolution scan exposes in fine detail,” explains Farahat. “We consider it lost information from the image and use specialist software to restore that information based on predictive data from adjacent frames. Viewers expect to see high-resolution images, so we cannot offer them anything less than perfect condition.”

The 300 iconic drama, comedy and musical films in the next phase were produced between 1941 and 1995, with several of them featuring renowned filmmaker and actor Farid Shawqy: The Midnight Driver (1958), The Thug (1957), His Majesty (1963) and Shaweesh Noss El-leil, aka Midnight Sergeant (1991). Restoring all of them to their former glory will take three years, after which a selection will be screened at film festivals; some will be given a wider public release so that cinema lovers can enjoy them once more.