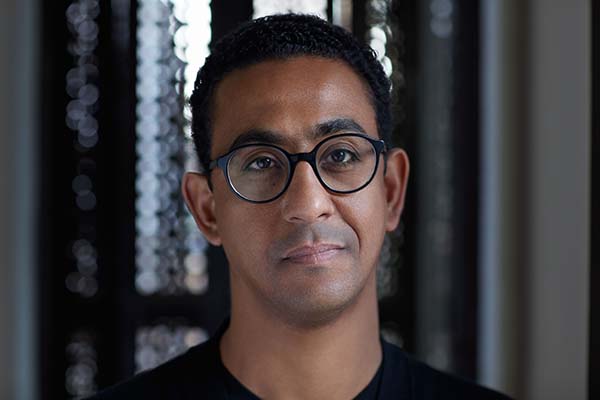

A new wave of filmmakers has emerged in the Arab world over the last decade or so, few of them with more critical acclaim and financial success than Marwan Hamed. The award-winning Egyptian talks to Shifa Naseer about being a modern-day director, the rise of the horror genre, and his upcoming film 'Kira & El-Gin'.

To outsiders, it seems obvious that Marwan Hamed, born into a media family, would choose to work in the same field. His father, Wahid Hamed, was a prominent producer and scriptwriter for Egyptian cinema, and his mother, Zeinab Sweidan, a well-known journalist. Despite being exposed to filmmaking from an early age, however, the path was neither obvious nor easy for Hamed.

“Back in the ‘90s, it wasn’t common to enter the film industry. It was a high-risk business then, and it still is. It is not an easy profession. But I thought I would be lucky to have my hobby as my profession, and if not this, I would not be successful in anything else,” he says.

After graduating from the Higher Institute of Cinema in 1999, Hamed began his career as an assistant director on Souq Al Motaa (1999). The film revolves around Ahmed, who works in a printing press and decides to travel to earn a living.

What sets Hamed apart from his peers is his experimental bravery, especially with literary adaptations. The first feature film he directed was The Yacoubian Building, based on the Alaa Al Aswany novel, in 2006. It is reported to have been the most expensive Egyptian film ever made, and generated over $4m around the world, screening at the Berlin International Film Festival, the Cannes Film Festival and the Marrakech International Film Festival.

Today, Hamed is an established filmmaker in Egypt, with a number of award-winning projects to his name. His most recent film, Blue Elephant: Dark Whispers (2019), is a sequel to his 2015 thriller The Blue Elephant, a box-office hit that grossed more than EGP 102m ($6.4m) in the Arab world.

The film is based on a 2012 novel by Egyptian writer Ahmed Mourad. It tells the story of Dr Yehia, a psychotherapist at Al Abbasia Hospital who treats the criminally insane, and whose best friend becomes a patient. Trying to help him, Yehia unravels mysteries he never thought existed.

“It was a great hit, and the plot of the horror/thriller novel was not very common at the time in Egyptian cinema. We decided to adapt this novel into a film in 2014, but there was uncertainty over how the audience would receive the film, since the horror genre wasn’t that popular with the masses at the time. To our surprise, it was a huge hit.

“The success encouraged us to make The Blue Elephant 2. The sequel was a challenge, as we had to live up to the expectations of the audience who had grown quite attached to the film.”

The sequel continues the story of Dr Yehia, who meets with a new inmate in the psychiatric hospital. This time, his life is turned upside down after the inmate predicts that the death of his entire family is only three days away.

“The sequel also proved to be a hit. If you add one and two, the series was successful not only in Egypt but also the entire Arab region,” says Hamed. The budget of the film was around $4m.

Hamed used an ARRI Alexa camera for The Blue Elephant: Dark Whispers, while for The Blue Elephant, he used both Red EPIC and ARRI Alexa. Visual effects for The Blue Elephant were created by BUF, a French visual effects and animation giant.

The Blue Elephant won nine awards at the 41st Egyptian Film Association Festival, with Hamed bagging Best Director and Best Film awards. At the 2015 Luxor African Film Festival (LAFF), the film was awarded the Grand Nile Prize for the Best Long Narrative Film. The same year, it received the Special Jury Award at the Brussels International Fantastic Film Festival (BIFFF).

Hamed is currently shooting Kira and El Gen in Egypt, though filming has been paused due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The release date has yet to be announced.

Hamed says: “I’m not going to talk much about this film, since we are yet to complete it. It is based on a famous novel called 1919, written by Ahmed Mourad, and revolves around the 1919 revolution in Egypt. Around 30% of the film will be in English, because the film is about a revolution that happened a hundred years ago in British-occupied Egypt.”

He has a big production team, Hamed reveals. “It really depends on which scene we are shooting. For instance, some scenes require a lot of extras on set so it could extend to a thousand on one day. On other days, it could be limited to less than a hundred. It keeps on changing.”

Hamed is known for his successful adaptions of sophisticated literary works. Asked what genre of film he most enjoys making, he remarks: “Whatever takes me out of my comfort zone; anything that puts me in a position where I can discover something new and experimental is where I like to work.”

Hamed graduated from the Higher Institute of Cinema in 1999, making six short films while studying. To afford this, he worked part-time.

“Making short films needed a certain amount of money and as a student, you don’t have that. I used to study in the morning and work as an assistant director in my free time to make money. One of the most important things we got to do there was a chance to make a film. That’s not something you get to do unless you are in a film school, especially in the ’90s when films were mostly 35mm.”

With multinational companies expanding in the Middle East and the advertising industry changing, Hamed gained a lot of work experience. “Advertising started booming and marketing changed. To shoot commercials, the multinational companies brought directors from all over the world to Egypt. In the late ‘90s and early 2000s, a lot of filming, especially TV commercials, took place. We were introduced to a lot of foreign crews that came to shoot in the country. My ability to converse in English helped.”

In those days, processing 35mm footage was expensive. “There was no digital then. The video did not have the quality digital format has now. So it was a privilege to be able to work and finish a cinema project.”

The most difficult part of filmmaking, according to Hamed, is figuring out if something you find interesting will be interesting enough for the viewer as well. “The important thing is, whatever I pick up – a subject or topic or film – can it reach an audience or not? I always try to make something interesting for the audiences.”

Hamed usually works with the same team, feeling that having familiar people around makes filmmaking more convenient and efficient.

“It is not easy to find a creative team you can work with multiple times. It is very rare that you have a team where everyone understands each other and has the same vision. I have had the same costume designer for all my films, and I think she adds value to all my works. I’ve been working with the same writer for the past six films. I have worked with only three or four art directors and, throughout my career, with only two directors of photography.”

However, he and his team are conscious of the fact that they could fall into the trap of being repetitive. “Each of us, individually, wants to produce something that is different and unique.”

As production style has changed over the years, distribution has evolved with it. With the rise of OTT platforms like Netflix and Shahid, the audience has also become more aware of the films being produced, Hamed notes. “There is a demand for Egyptian cinema and people like watching Egyptian films, regardless of what is being shown. But with all the OTT platforms, audiences are also aware of international cinema and the quality of work there. With this, they also understand if it’s a fresh idea or not.”

The future of the cinema business, not just in Egypt but across the world, is grim now. “With Covid-19, theatres and the cinema industry have been hit, but the television industry and OTT platforms thrived. Our business depends on making people step out of their homes to spend two hours of their time in theatres, buying not-so-cheap tickets. So, we have to make sure that when people come to theatres, they really have an enjoyable and memorable experience,” says Hamed.

He thinks the younger generation is more difficult to please. “There is demand for Egyptian cinema, but are we appealing enough to the younger audiences? They have a lot of choices now. I think Egyptian cinema is trying to stay young and constantly trying to appeal to the young audience.”

Hamed does not focus on making local or global films; it is the process of filmmaking that is important to him. “In every film, there must be some sort of experimentation, because we don’t know what is going to work or not going to. So I don’t think about whether the audience is Egyptian or Arab or international, or whether a film makes it globally or not.”

Hamed believes he has a duty to raise awareness through his films. “I think cinema is the real medium of expression that can help break stereotypes. But, of course, you have a responsibility towards your society – to raise awareness about issues that are seldom spoken of. For instance, sexual harassment is something that is being discussed now in a powerful way.”

On the government not doing enough for independent filmmakers, Hamed notes that independent cinema needs to be free from state control.

“I think independent cinema in Egypt has been very successful. These films managed to get funds from film festivals, and from local independent Egyptian and Arab producers. Independent filmmakers should be able to discuss unconventional topics. If you are dependent on the government, it puts filmmakers in a box,” he says, referring to Egypt’s censorship laws.

Hamed has successfully carved out a space for himself in Egyptian cinema. In over 20 years, he has made short films, feature films and ads, and in 2007 he co-founded production house Lighthouse Films.

Filmmaking is his source of income, and he manages to secure funding from local Egyptian producers. “That is why it is important for me that the film reaches an audience, because it is a way for me to secure funding for the next film.”

His advice to aspiring filmmakers: persevere.

“We are in an era where anyone can shoot films on phones, upload them on YouTube and get an audience. The legendary filmmakers, actors and producers did not always think they were making great films, but they didn’t stop. They just continued to make films – because the excitement of not knowing how people are going to react to your film is part of this business.”