UAE-based filmmaker Moe Najati’s documentary chronicles the traditional Emirati fishing method Daghwah, which is now on the decline. Vibhuti Arora brings you some highlights of the film Moe Najatis recent documentary, Daghwah, documents a traditional Emirati fishing method and the community revolving around it. Now in decline, the tradition is kept alive by a handful […]

UAE-based filmmaker Moe Najati’s documentary chronicles the traditional Emirati fishing method Daghwah, which is now on the decline. Vibhuti Arora brings you some highlights of the film

Moe Najatis recent documentary, Daghwah, documents a traditional Emirati fishing method and the community revolving around it. Now in decline, the tradition is kept alive by a handful of fishermen living off the coast of Kalba, for whom fishing is the main livelihood. An official selection for at least five film festivals in Europe and North America, the film brings to life a dying tradition.

I used to drive quite often to Fujairah and would see these colourful trucks parked on the shore. What caught my eye were the bright colours of these lorries, which I thought were abandoned. I stopped by one day and went closer to the beach to see more, and saw at least five to six trucks parked on the shore, very close to the water, and saw fishermen who owned these trucks.

Thats when I began to dig deeper into it and started researching the subject. I spoke to the fishermen to learn more about this practice, and the stories I heard were quite interesting. So I began to explore the possibility of making a documentary about it, Najati explains.

While doing the groundwork for the project, Najati forged friendships with the fishermen to get them to talk about their lives in front of the camera. The testing for cameras and equipment began in earnest and Najati zeroed in on the RED Dragon.

I love to shoot with the RED. Its a big camera, but we had a nice set-up to pull the project through. My DoP, Asif Limbada, and I decided to work with vintage anamorphic Kowa lenses, which was a rather unusual combination with the RED Dragon. When I saw the output of these lenses, I immediately decided to go with the look the anamorphics would lend to my stories.

This choice of lenses made the process of grading quite complicated for Azin Samarmand, the colourist at Montage, a post house in Dubai, who worked on Daghwah. Samarmand explains that the output with vintage anamorphic lenses is quite different to what you would expect from digital design lenses.

These lenses are designed for film, and putting an anamorphic on a RED sensor gave a totally different look to the documentary. The format, the light that it gathers is not usual. With regular, normal lenses, what you see is what you get, which may not be the case with anamorphics. Having said that, they do enrich the texture of the footage and add new dimensions to it, which the ordinary eye wont catch.

Najati agrees that vintage lenses have their own traits and aspect ratio, so there was a lot of experimentation involved at the filming stage to arrive at the best combination. Anamorphic lenses distort the film in an artistic way and give it a richer texture and vignette, he points out.

The experimentation did not end at filming, even in post there were quite a few challenges, but the experiment was definitely worthwhile, agree Najati and Samarmand. The images appeared vignetted and the shadows were richer, with the contrast brought out vividly. Since the film was shot in summer, the sky had no contrast and appeared flat, which the colourist was required to fix in post-production.

It took us longer to grade this film than normal. For an 11-minute documentary, we took almost five days to do the grading, explains Samarmand.

The files I would receive were massive in 6K, and we had to bring them down to 2K. I worked directly on the 6K files, which was an advantage, and it allowed me to pull more information and detail for final output in 2K. Regenerating the lights and colours in grading was one of the key requirements of the project.

The RED Dragon gives 15 stops of dynamic range, which helped to handle the 6K footage shot on it. Had it been any other low-end camera, points out Samarmand, it wouldnt have worked.

I loved working on this film. We had a shot of a car in a corner of the beach which had to be colour-graded and corrected. There were so many different elements in this single shot, right from the overly bright sky with the sunlight reflecting on the car chassis. We had to balance these and add colour to water.

While doing all this, we had to ensure that the images had continuity and had no jumping of colours. These were the main challenges, but I wouldnt have chosen to do it any other way. At the end of it, what we got is a fantastic documentary.

Daghwah is a dying tradition, with fewer fishermen engaging in it, explains Najati. The coast is shrinking, and so are the varieties of fish, in the wake of ecological changes.

This type of fishing is done at the coast up to a distance of a few kilometres. The fishermen set out to fish every day around 6am, but its not every day that they come back with fish.

Najati and his team would set out early, by 3 or 4am, and wait for light to come. On shore, the camera was set up on tripods. A DJI stabiliser was also used for some shots, but shots in the sea had to be set up on a boat.

We could only do handheld shots on the boat. There used to be three workers, the main fisherman and the two of us the DP and myself. There was not much room on the boat, as the net used for Daghwah is huge and takes most of the space, Najati explains.

The film was edited by Najati himself on Adobe Premiere Pro.

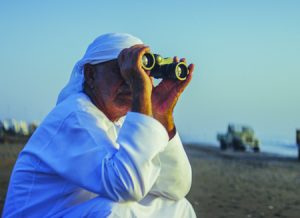

I took some time to decide who I would finally shoot with. Out of the many fishermen interviewed, I shortlisted six, based on who had the best stories to tell and their voice clarity and screen presence. Most of them were very welcoming, and were happy to be a part of the documentary. For the film, we have retained just one main character and his team. He started fishing after World War 2 and has been actively fishing ever since, says Najati.

Najati’s relationship with film goes back to when he first held the camera in university. As a visual arts student, filmmaking was one of the subjects he studied at the American University of Sharjah.

Films were a part of the course, but I got drawn towards it more than anything else. I started my career as a photographer and then branched into filmmaking, he says.

Najati enjoys making documentaries and has released two independent productions Daghwah and Fifty 4 he feels his true calling is drama and action. Comedy, although a popular genre, is a difficult one because as he sees it, making people laugh is not easy. Najati is now developing a full-lenght feature on human behaviour and political correctness.