MBC Group CEO Sam Barnett gives BroadcastPro ME a candid glimpse into the challenges of the past three months and the strategy ahead.

MBC Group CEO Sam Barnett gives BroadcastPro ME a candid glimpse into the challenges of the past three months and the strategy ahead.

When MBC Group Chairman Sheikh Waleed bin Ibrahim Al Ibrahim was detained along with several other royal members and high-profile businessmen from the Kingdom at the Ritz-Carlton as part of an anti-corruption drive in November, there was only one thing on CEO Sam Barnetts mind the show must go on. Waleed was released in January this year, although the terms and conditions of his release remain the subject of speculation.

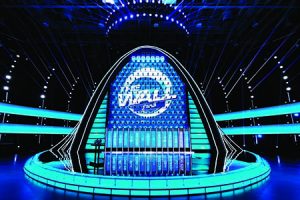

MBC Group is one of the finer examples of a commercially successful broadcast operation in the MENA region, and it has continued launching a steady stream of new programmes and formats in the new year. Even as we went to press, production was in progress at MBCs Dubai Studio City facility for The Wall, an Endemol Shine format that the broadcaster has franchised and brought to the region for the first time. The fabulously lit, five-storey pegboard, built to the exact standards of its international counterpart, was assembled in Italy and brought to Dubai.

The Wall launched on MBC 1 on Valentines Day, hot on the heels of the Beirut grand finale of The Voice Kids, which crowned 10-year-old Moroccan Hamza Labeid as the winner and drew in an estimated audience of 100m viewers across the region. Anecdotal media stories describe cities across MENA coming to a standstill to watch their young compatriots perform.

It all comes down to content. There is a lot of talk about structural changes and viewership and platforms, but ultimately, the strength of what we do comes down to our content

Alongside these shows, the broadcaster has several other new initiatives in parallel from Wizzo, its games portal to Goboz, touted as the regions largest and safest kids VOD. MBC also has several original productions lined up for Ramadan on its Shahid Plus platform and is in the process of setting up a disaster recovery facility in Cyprus. Political upheaval has clearly not slowed down the broadcaster.

It all comes down to content, says Sam Barnett around 15 minutes into our interview at the broadcasters HQ in Dubai Media City.

There is a lot of talk about structural changes and viewership and platforms, but ultimately, the strength of what we do comes down to our content.

Theres no arguing with that approach, as the industry has watched with admiration over the years as the Saudi broadcaster has engaged a growing audience across the region and beyond, with a compelling mix of international and locally produced shows, drama series and more. Recent programme and platform launches, however, come in the face of some unprecedented challenges, the foremost being Sheikh Waleeds detention at the Riyadh Ritz-Carlton.

This was followed by the more recent announcement that MBC no longer holds the rights to Saudi Professional League football matches, which it had secured as part of a ten-year $1.09 billion deal in 2014. The contract was handed over last month to state-owned Saudi Telecom Group (STC) for a reported $1.8bn by KSAs General Sports Authority.

In a conference room overlooking a clear winters morning over the Palm, Barnett talks about this turn of events.

For Ramadan this year, we have Al Assouf, a Saudi historical drama set in the 1970s, featuring the famous Saudi comedian Nasser Al Qassaby. We are so confident about it being successful that we have already shot Season Two

The strategy for sports has changed in the Kingdom. When we took the rights in 2014, the idea was to go with the model that worked elsewhere in the world, which was to try and create premium league football, encrypt it and generate pay revenues, which would then feed back to the clubs. They were looking to develop the football sector in Saudi. I think, since then, the environment has changed and the authorities and the Federation want to maintain free-to-air football. Clearly, we had bought the rights on a different model so we were expecting something to change, so we will adapt to that, but this has not necessarily come as a shock to us. We have been in discussion with the authorities now for 18 months on how we navigate this change in strategy. We are still talking, but as is evident from the announcement, there was a clear shift.

And what happened to the billion-plus dollars offered to purchase the rights?

Thats still part of the discussion, says Barnett, without elaborating.

A week following Sheikh Waleeds release, Barnett does not make light of MBCs ordeal following the detention but stresses the innate resilience of the 26-year-old organisation.

I challenge you to look at MBC programming prior to November 4 and onwards. You will not spot any difference in our editorial or programing policies. There has been absolute consistency. And when most organisations would have wobbled with their chairman not being accessible, the employees here were robust. The institution is strong; we are cash flow positive and the programming has continued. We have been affected by this, morally and emotionally, and we have been through difficult times, but the work has continued.

There was a lot of media interest locally and internationally as to whether MBC is in trouble. A few advertisers may have had concerns, but matters have since calmed down when they saw that it was business as usual at MBC. The whole issue cleared up at the right time as advertising budgets are being finalised, and the finale of The Voice Kids and the launch of The Voice are a testimony that all is good and Sheikh Waleed is back.

While there has also been a lot of speculation in the media about the terms and conditions of Sheikh Waleeds release, Barnett confidently says: Sheikh Waleed is out; he has been exonerated of any wrongdoing. He has kept all of his shares and will retain management control of MBC. He also stresses that the things that MBC and Sheikh Waleed have been pushing for are aligned with policies in many countries if this is a Saudi-owned institution, it is one they can be very proud of.

In the meantime, MBC Group has focused on remaining profitable. In 2014, while the rest of the Middle East and South Asia was overwhelmed by glamorous television dramas from Turkey, MBC established O3 Medya in Istanbul to undertake Turkish productions.

I was on a trekking holiday in Ethiopia. Each village I would get to, there would be a shop selling matches, soap and there would be a TV hooked up to a car battery with MBC Action playing

When the demand for Turkish drama began to soar, we thought we would hedge our bets by having a production house in Turkey. That has worked very well. Today, we have Antah Watani (The Traitor), which is the number one show in Turkey running on our screens at the moment. We are producing what will be the largest Turkish production ever, which is Sultan Al Fateh.

Over the years, Arabic drama has also increased in popularity. The production values for drama have improved with the growth in the advertising market and more revenue per episode. For Ramadan this year, we have Al Assouf, a Saudi historical drama set in the 1970s, featuring famous Saudi comedian Nasser Al Qassaby. We shot it in Abu Dhabi within the twofour54 premises, and we are so confident about it being successful that we have already shot Season Two.

But productions cost money. A Turkish drama episode costs hundreds of thousands of dollars per episode, he says. To add to a Middle East broadcasters woe, along with the advertising downturn, are the lack of a robust ratings system and tougher laws to counter piracy.

Advertising revenues dropped last year. We will generate the same ratings this year as last year, and we deserve the advertising budgets. We have been profitable for many years despite the decline in advertising and the shock we received last year.

The measure MBC took, besides actively working with the anti-piracy coalition to bring pirates to book, was to expand into more markets like Africa with more targeted content, thereby attracting more targeted advertising. To do that cost effectively, it moved to spot beams.

For many years now, we have been reaching out to 140 million people each day, but we only sold advertising for a small percentage of those eyeballs. We sold in the Saudi market and more recently in the Egyptian market, but in North Africa, where we have four of the top ten channels now, there is huge potential. Algeria has the potential to grow significantly, with 37 million people, four million barrels of oil per day and an economy that has a huge amount of pent-up latent demand. Brands will rush in there, but the fact that we were stronger but were not able to generate advertising revenues for that market was a weakness.

If we cannot tackle piracy, then investing anymore in pay TV will be difficult, because you cannot make a return. We would urge regulators to take a stand to defend intellectual property rights otherwise we can all pack up and go home

We had two options. We could go and launch MBC Algeria and MBC Morocco, and try and use the content to attract people away from the main channels. That is quite an expensive strategy. Ultimately, you are competing against your main channels. Like with MBC Masr in Egypt, it had to pull people away from MBC 4 and MBC 1. The move was successful, but the point was that it was an expensive way of doing it.

MBC decided to move to spot beams onto 26 degrees East (Arabsat Badr 7), and 7 and 8 degrees West (Eutelsat). This meant it could now have targeted programming and advertising.

If you could use the satellite and essentially divide the feeds into two, then we can use our existing channels to target those in North Africa at the flick of a switch. That is what is happening, says Barnett.

We are now able to sell North Africa advertisements on those spot feeds. Last year, it was a small number and this year, it will be a bigger number, and in 2019, it will be an even bigger number.

And over time, and particularly as those markets develop advertising wise, this would have been a good thing to have done. Advertisers want to get data on markets. The point is Saudi is being measured. There is a people meter in Morocco, and in Algeria, it will come as the market develops.

The move to Arabsats spot beams had its nervous moments, Barnett confesses. The town of Benghazi surprisingly informed Barnett that his gamble had paid off. We were slightly nervous when we moved to spot beams. We cut our channels off the wide beams and asked everyone to move to the spot beams. It was potentially traumatic. The fact that I am sitting here talking to you confirms that it has worked and that 57 million TV households actually retuned.

Clarifying how MBC knew, Barnett explains: At the time, we looked at online search trends for MBC frequencies, and we found this massive spike from Benghazi. When we saw that, we knew it had worked. Both the spot beams drop off, and unfortunately, people in Benghazi are outside the coverage. They can still watch MBC, but they need a bigger dish. The sudden massive spike from Benghazi on the search trends, by logical deduction, meant that had Riyadh or Marrakesh faced a problem, there would have been an even bigger spike because of sheer population.

While building audiences in North Africa will remain a focus in 2018, the rest of Africa has been a revelation. On a hiking trip in Ethiopia, quite by accident, Barnett discovered that MBC had audiences in Africa too in big numbers.

We found out almost by chance that we had a big audience in Africa from the [satellite] overspill. I was on a trekking holiday in Ethiopia. Each village I would get to, there would be a shop selling matches, soap and there would be a TV hooked up to a car battery with MBC Action playing. We found out that MBC Action was the largest channel in Ethiopia, a country of 85 million people. At the same time, we found that the channel was popular in Mali, northern Nigeria and West Africa, among other regions.

Subsequently we bought rights for movies for Sub-Saharan Africa and we launched MBC+ Power two years ago. We are monetising the market through the channel. We are interested in every single market, from Europe and Latin America to Africa, the US, Australia, New Zealand and so on. This is a sector that grows 20% each year.

MBC is looking to ramp up efforts even further in the wider Arab world, as well as North Africa.

Localisation of content and growing North Africa are two big challenges. We have a good deal with Etisalat, as we do with a number of telcos across the region. We work in Lebanon with broadcasters there. We are popular in many countries. In Iraq, for instance, we are the largest channel with MBC 1 and MBC 4.

There is a secular growth of advertising as economies such as Algeria develop. For Shahid and our other digital initiatives, we have employed more people in Jordan, where we do software development. However, one of our biggest challenges are the international players who dump content at very cheap prices. Previously, it was sufficient to be a good local competitor. Now you cannot just be good, you have to be excellent while ensuring cost efficiency. We are exploring automation solutions and have plans to use our disaster recovery unit in Cyprus more efficiently.

In the meantime, Barnett also confirms that MBC has no plans to expand into the pay TV space, for a number of reasons, piracy being one of them. He particularly points a finger at a new entry in the market, called Beoutq.

Beoutq is a new box that I understand is showing international sports programmes for which they do not have rights. Now, they are also taking MBC’s encyrpted channels and OSN’s as well. You pay $108 for the box and you get everything free for the first year. I believe it is available in Saudi Arabia and possibly elsewhere. If we cannot tackle piracy, then investing anymore in pay TV will be difficult, because you cannot make a return. We would urge regulators to take a stand to defend intellectual property rights otherwise we can all pack up and go home. Fortunately, we dont have a huge exposure within pay and we are not in sports much longer either. Pay is a strategy we may have pursued if there was a clear defence of intellectual property rights.

Apart from piracy and the threat of FAANG, Barnetts team is looking at data, the one big lacuna across the regional industry.

We have undertaken a big data initiative to make up for the lack of quality research in the region. We do not yet have minute-byminute dissection of ratings across countries, but that is changing. We will be using technology including data from telcos and people meters. We already have the structures ready for this incoming data that will generate all sorts of growth possibilities.

Possibly the biggest challenge facing Barnett is demographic, with more than 28% of the Middle East population aged 15-25. The region is also second in the world in terms of daily YouTube video views, with more than 310 million. Broadcasters have to make sure content and the right sort of content is reaching younger users and transitioning boomers and Gen X.

Barnett responds by highlighting the flip side of good content the innate strength of the staff in the organisation, drawn from 65 nationalities.

Our production teams are drawn from the region and target audiences. If you walk around the building, you will see the diversity. Without that, we could become outdated very quickly. Diversity keeps us young and relevant, but it is also a strategic decision. The last three months have been challenging, but what I saw was a real bond among the people here. We have emerged stronger.

The political situation around MBC Group and other Saudi organisations remains volatile, with conflicting media reports, but there is no doubting the inherent strength of MBC as we walk past the broadcasters bustling offices and studios.