The word convergence has been used around the television business for decades, without anyone really understanding its potential. With the advent of file-based workflows and the proliferation of IP circuits, it appears that we are finally reaching the point where broadcast signals can be transmitted over newer telephony infrastructures As the technology evolves, it becomes […]

The word convergence has been used around the television business for decades, without anyone really understanding its potential. With the advent of file-based workflows and the proliferation of IP circuits, it appears that we are finally reaching the point where broadcast signals can be transmitted over newer telephony infrastructures

The word convergence has been used around the television business for decades, without anyone really understanding its potential. With the advent of file-based workflows and the proliferation of IP circuits, it appears that we are finally reaching the point where broadcast signals can be transmitted over newer telephony infrastructures

As the technology evolves, it becomes practical and effective to move content as data over IP circuits for more applications. The underlying driver for this is the same as one of the key drivers behind the file-based revolution in broadcasting: it allows the use of more standard, commoditised products rather than proprietary and bespoke technologies.

To move television signals between centres or from a sports stadium back to the studio traditionally required co-ax video circuits. These were really only of use to broadcasters, so the telcos which provided them charged high fees, in part because of the cost of maintaining a little-used infrastructure.

Once we reached a point at which video could be carried as packetised IP, in real-time or fast enough to be practical, then it could be sent down any bearer with sufficient free capacity. Those circuits and routings might at other times be used for other data operations: for banks, airline reservations, the public internet or any other application.

These are commodity circuits, so the price is inevitably driven down. Competition between telcos and specialist data carriers also leads to lower prices and improved customer service. That customer service offering includes the ability to guarantee bandwidth, quality of service, and consistency of routing and latency all of which are important to broadcasters.

The move to IP delivery started with non-real-time services. As broadcasters developed file-based workflows they preferred content programmes and commercials to be delivered as files as it saved the labour-intensive stage of ingest and QC from tape. Producers were equally keen on the idea because it saved them the labour-intensive stage of making delivery copies, not to mention the cost of the tape stock and shipping.

High-speed file transfer software brought the two together by accelerating the data flow to make the best of the bandwidth and reduce costs. There is also confirmation management software at each end of the delivery to ensure that sender and receiver were confident the content arrived where it was supposed to, when it was supposed to, and without any chance of anyone else seeing it on the way.

The real benefit comes when it is practical to use IP circuits for real-time transmission, in particular for contribution circuits from remote broadcasts such as sports stadiums or major news events. This tackles head-on the costs of using monopoly services over dedicated fabric. It means a broadcaster can book, and pay for, just the capacity needed at the time. It also means the broadcaster can determine the balance between bandwidth (and therefore cost), image quality and latency required for that specific project.

While a few very prestigious projects will use huge amounts of bandwidth to transmit an uncompressed signal back to the studio, most will choose some form of compression. Today, contribution codecs are available using JPEG2000 or 10-bit H.264 4:2:2 which can provide more than adequate quality for primary broadcast albeit at a different balance of bit rate, price and latency.

Conversely, given the availability of large amounts of IP capacity and the quality and low latency of modern codecs, some are suggesting that multiple contribution circuits could transform the way television covers sport. If 300Mb/s JPEG2000 is effectively transparent, why not ship all the camera signals back to the studio and mix the programme from a permanent control room rather than send a truck to site, goes the argument. A 10Gb/s fibre circuit would be sufficient for as many as 15 cameras, plus all the audio, intercom, control and return feeds around them.

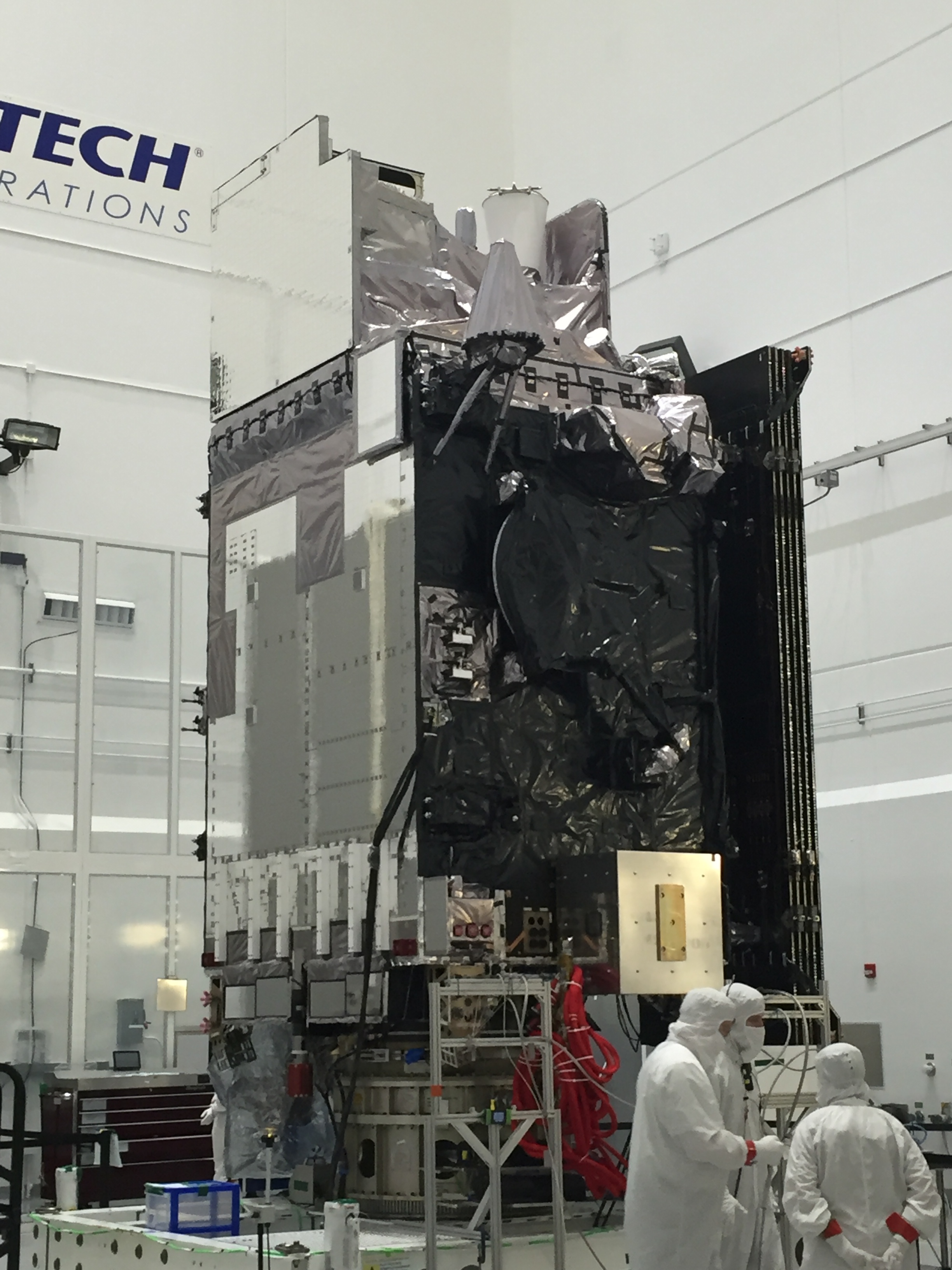

The practicality of sending real-time contribution quality over fibre does not mean that the days of satellite uplinks are over. There are times when a satellite is the best path, not least at venues which do not have an access point to fast IP fibre. Satellite is also a more cost-effective solution when you are sending to multiple destinations. Today the break-even point might be six or seven destinations before satellite becomes the most cost-effective option, but that is not uncommon.

On the other hand, sometimes establishing a satellite uplink can be a challenge. It requires clear line of sight to the satellite, which can be difficult to find in some cities. If fibre is available it can save a lot of cable rigging.

What it does mean, though, is a real convergence inside the broadcast infrastructure, at both ends of the circuit. It is imperative that the architecture is based on both IP and real-time video and audio, and there is a free flow between the two.

In the simplest of cases, it could be argued that there is no need for convergence: the remote broadcast is managed in video with just an encoder on the output, with a matching decoder at the point where it reaches the studio. That would work for the main contribution circuit, but there is the possibility of adding much more value by further integration.

It is common, for example, for broadcasters to brand their sports coverage with distinctive motion graphics. These are created at headquarters, and can be uploaded into the OB truck which may have been working for a competitor broadcaster the day before over the IP circuit. Some contents of the production servers may be needed back at the studio before physical disks can be transported. That content can be sent alongside the programme stream. There may be several versions of the content: with and without presentation, streaming versions, multi-language branded basically tailored for each team on the spot. This far exceeds current methods of produced and clean feeds being sent out.

The real requirement, then, is for an infrastructure that can bridge the two worlds and such technologies will become an important part of systems engineering for both broadcasters and telcos. Moving content between broadcast and IP domains has to be as simple and transparent as the video distribution amplifier is today.

The Sultanate of Omans national telco OmanTel, which needed to build out a new country-wide contribution and distribution network for broadcasters in 2011, elected to do it over IP circuits, bridging into the broadcast world. It undertook this project with the Selenio media convergence platform, which has audio, video and IP backplanes and can process signals and deliver to any domain.

Whether for permanent or temporary links, it is clear that using industry standard IP connectivity offers real benefits in cost and convenience, without serious impact on quality or operational flexibility. The ability to use commodity technology and services from competing providers will continue to drive down prices, which ultimately will lead to more and better coverage for viewers.

The challenge for the broadcaster is to clearly understand these newer transport options, their limitations and develop technical strategies to take advantage of this expanded and affordable connectivity for seamless, high-quality television.

Stan Moote is vice president of business development at Harris Broadcast.